When a life-saving drug runs out, who gets it? This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in hospitals across North America. In 2023, the FDA tracked 319 active drug shortages, with critical cancer medications like carboplatin and cisplatin in critically short supply. Oncology centers reported that up to 70% of patients faced delays or denied treatment. When there’s not enough to go around, doctors aren’t left to guess. They follow ethical frameworks-structured, evidence-based systems designed to make unfair situations as fair as possible.

Why Rationing Isn’t Just a Last Resort

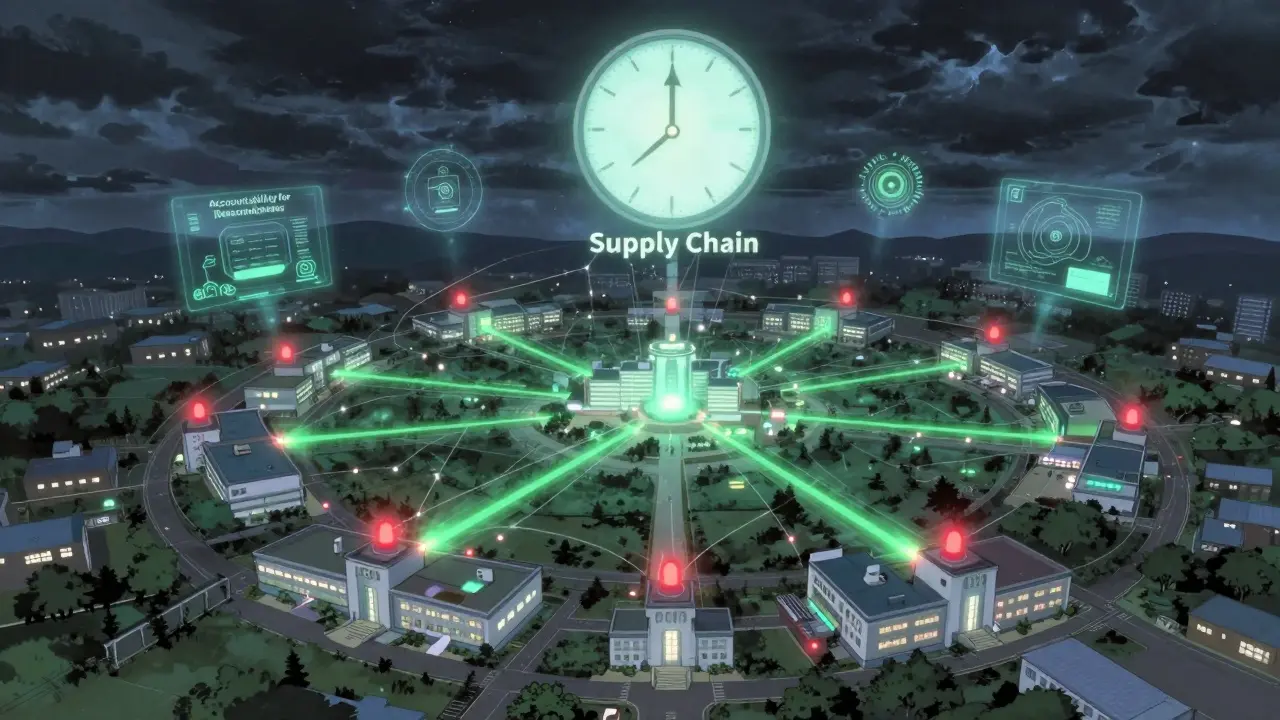

Medication rationing isn’t about running out of pills because someone ordered too few. It’s a systemic failure: a single manufacturer shuts down a production line, raw materials get delayed, or a company decides a low-margin generic drug isn’t profitable anymore. The result? A sudden, massive gap in supply. In 2011, there were 251 drug shortages in the U.S. By 2023, that number had jumped to over 300. Sterile injectables-especially cancer drugs, antibiotics, and anesthetics-make up nearly half of all shortages. Hospitals can’t just order more. These aren’t over-the-counter meds. They’re complex, tightly regulated, and often made by just two or three companies. When one falters, the whole system stumbles.The Ethical Frameworks That Guide Decisions

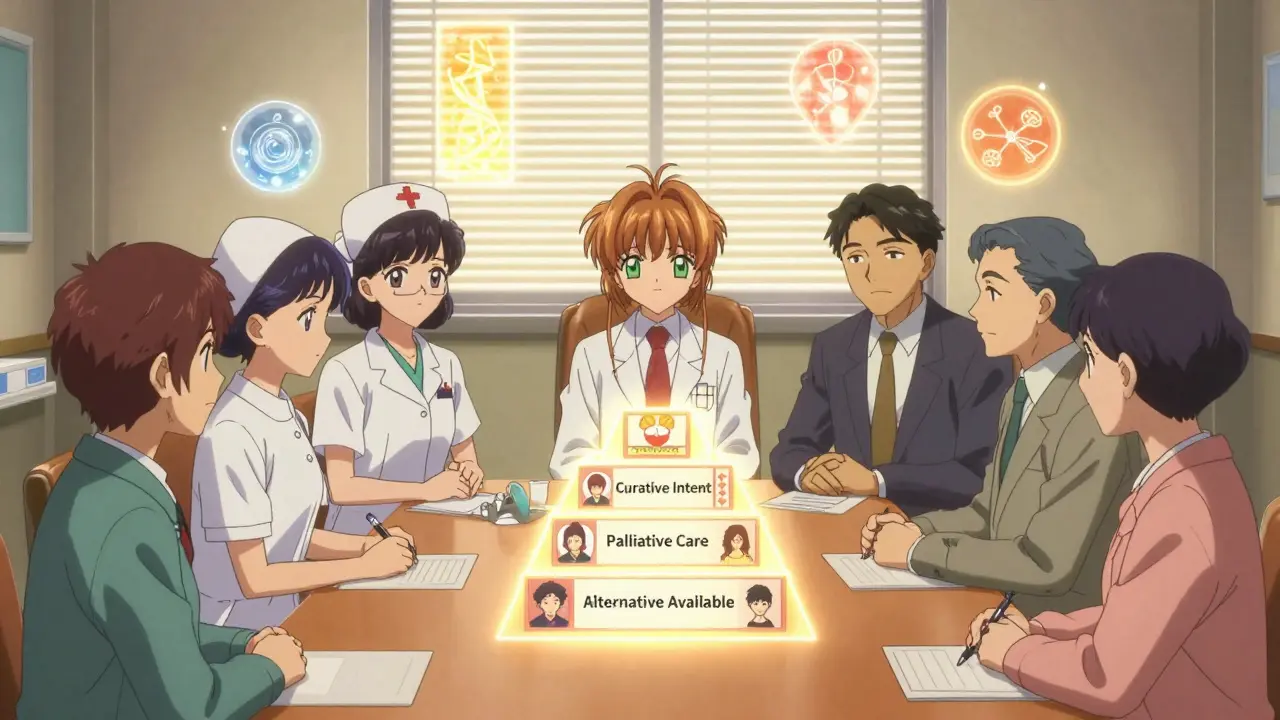

Without rules, rationing becomes chaos. One nurse might give a dose to a younger patient. Another might prioritize someone with better insurance. That’s not just unfair-it’s dangerous. That’s why healthcare systems rely on proven ethical models. The most widely accepted is the Accountability for Reasonableness framework from Daniels and Sabin. It requires four things: transparency (everyone knows how decisions are made), relevance (decisions are based on medical evidence, not personal bias), appeals (patients or families can challenge a decision), and enforcement (someone makes sure the rules are followed). In oncology, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) added disease-specific criteria. They don’t just look at who’s sicker. They ask: Is this patient being treated with curative intent? Is there an equally effective alternative? Will this drug significantly extend life? These aren’t abstract ideas. They’re used daily in hospitals to decide who gets the next vial of cisplatin.Who Decides? Committees Over Clinicians

The biggest mistake hospitals make? Letting individual doctors decide on the spot. That’s bedside rationing-and it happens in over half of all cases. A 2022 JAMA study found 51.8% of rationing decisions were made by treating teams alone. The result? Higher burnout, more moral distress, and glaring inequities. One oncologist in the ASCO forums shared: “I’ve had to choose between two stage IV ovarian cancer patients for limited carboplatin doses three times this month-with no institutional guidance.” The better way? Multidisciplinary committees. These teams include pharmacists, nurses, physicians, social workers, patient advocates, and ethicists. They meet before a crisis hits. They build protocols. They review cases. Hospitals with these committees see 32% fewer disparities in who gets treatment. A 2022 Mayo Clinic study showed 41% lower clinician distress scores when committees were active. But here’s the problem: only 36% of U.S. hospitals have standing shortage committees. And just 2.8% include an ethicist.

How Decisions Are Made: The Criteria That Matter

It’s not about age, income, or who shouts loudest. Ethical rationing uses measurable criteria:- Urgency of need-Is this patient’s condition deteriorating without the drug?

- Chance of benefit-Will this drug actually help? For example, carboplatin works best in early-stage ovarian cancer with curative intent.

- Duration of benefit-Will this extend life for months, or just weeks?

- Years of life saved-Giving a drug to a 30-year-old might save more life-years than giving it to an 80-year-old with multiple conditions.

- Instrumental value-In extreme crises, some frameworks prioritize healthcare workers to keep the system running.

What Goes Wrong? The Real-World Gaps

Even the best frameworks fail without implementation. Rural hospitals? 68% have no formal rationing plan. Academic centers? Only 32% lack one. That’s a massive gap. And when a shortage hits, it’s often the most vulnerable who suffer. A 2021 Hastings Center Report found 78% of rationing protocols ignore equity metrics for low-income, racialized, or rural patients. Someone in a small town might wait weeks for a drug that’s already being given in a big-city hospital. Another problem? Communication. Only 36% of patients are told they’re being rationed. Families don’t know why treatment was delayed. They don’t know if a different drug was tried. They don’t know how decisions were made. That erodes trust. ASCO’s 2023 update pushed hard for transparent patient communication. It’s not optional anymore.

What Hospitals Are Doing Right

Some places are ahead of the curve. Hospitals with formal protocols don’t wait for a crisis. They prep. They train. They simulate shortages. They use the “stepped approach” recommended by the American Journal of Bioethics:- Conservation-Use the lowest effective dose. Extend dosing intervals. Reduce waste.

- Substitution-Switch to another drug with similar effectiveness. For example, oxaliplatin can sometimes replace cisplatin in certain cancers.

- Rationing-Only when the first two fail, use the committee-based allocation system.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Keeps Happening

Drug shortages aren’t random. They’re structural. Three companies control 80% of the generic injectable market. If one has a quality control issue, dozens of hospitals are affected. The FDA requires manufacturers to report shortages six months in advance-but only 68% comply. And with generic drug profits shrinking, companies are dropping production altogether. In 2022, hospitals spent an average of $218,000 just managing shortages-buying expensive alternatives, paying for expedited shipping, training staff. The FDA’s new Drug Shortage Task Force is building an AI-powered early warning system. It’s supposed to cut shortage duration by 30% by 2025. The National Academy of Medicine is drafting standardized ethical metrics for allocation. Pilot certification programs for hospital ethics committees are launching in 15 states in early 2024. These are the first real signs of change.What You Can Expect Next

This isn’t going away. The FDA projects 25-30% annual increases in drug shortages through 2027. Cancer drugs, antibiotics, and critical anesthetics will keep being hit hardest. The question isn’t whether rationing will happen. It’s whether we’ll be ready. Hospitals that wait until a drug runs out to act will fail. Those that build committees, train staff, communicate openly, and track decisions will protect patients and providers alike. The goal isn’t to make rationing easy. It’s to make it fair.Is it legal to ration medications?

Yes, but only under strict ethical and institutional guidelines. Rationing isn’t about denying care-it’s about allocating scarce resources fairly when supply can’t meet demand. It’s legally protected when done through transparent, committee-based systems that follow established bioethical frameworks like Accountability for Reasonableness. Individual clinicians making unilateral decisions without oversight can face legal and ethical consequences.

Do patients ever get told they’re being rationed?

Too often, no. Only about 36% of patients are informed when their treatment is delayed due to a drug shortage, according to JAMA data. This lack of transparency causes mistrust and emotional harm. Leading ethics groups like ASCO now require hospitals to disclose rationing decisions clearly and compassionately. Patients have a right to know why their treatment plan changed, even if the reason is supply-related.

Can I request a different drug if my medication is on shortage?

You can ask, but it depends on medical suitability. Not all drugs are interchangeable. For example, carboplatin and cisplatin are both used for ovarian cancer, but they have different side effects and effectiveness profiles. Your doctor must evaluate whether an alternative is safe and effective for your specific case. Hospitals often use substitution as a first step before rationing, but only when clinical evidence supports it.

Why don’t hospitals just order more of the drug?

Because they can’t. Many of these drugs are made by just one or two manufacturers. If production stops due to quality issues, regulatory shutdowns, or business decisions, there’s no backup. Generic injectables are low-profit, so companies prioritize more profitable drugs. Even if a hospital orders extra, the manufacturer may not have the capacity to supply it. This isn’t a supply chain glitch-it’s a systemic flaw in how generic drugs are produced and priced.

Are some patients prioritized over others because of their age or income?

Official protocols prohibit this. Ethical frameworks focus on medical need, likelihood of benefit, and potential life extension-not age, income, or social status. But in practice, disparities still occur. Rural hospitals, under-resourced clinics, and marginalized communities often get less access. A 2021 study found 78% of rationing plans don’t include equity metrics. That’s why national efforts are now pushing for standardized, bias-resistant allocation tools.

9 Comments

Jane Lucas

December 27, 2025 AT 14:07my cousin got denied chemo last year because they ran out of cisplatin. they just told her to come back next week. she cried in the parking lot. no one explained why. no one apologized. just silence.

dean du plessis

December 29, 2025 AT 12:51it’s wild how we treat life-saving meds like scarce coffee beans instead of human rights. we’ll ration oxygen in a pandemic but act shocked when cancer drugs disappear. the system’s broken, not the patients.

Nicola George

December 31, 2025 AT 12:36so let me get this straight - we’ve got AI systems predicting shortages but no one’s holding the 3 companies that control 80% of the market accountable? lol. sure. next they’ll say the patients are ‘too emotional’ for their own good. 🙄

Miriam Piro

December 31, 2025 AT 19:33you think this is about ethics? nah. it’s about profit margins. the same pharma giants that make billions off patent drugs quietly kill generic production lines because they’re ‘not profitable enough’. then they sell the ‘alternatives’ at 10x the price. the FDA? they’re asleep at the wheel. and the committees? just PR theater to make doctors feel less guilty. they don’t save lives - they save lawsuits. the whole system is a pyramid scheme built on sick people’s suffering. you want transparency? start by publishing every single contract between manufacturers and hospitals. i bet you’ll find a lot of ‘confidential’ clauses hiding the real reasons.

Kylie Robson

January 2, 2026 AT 08:33the Accountability for Reasonableness framework is fundamentally flawed because it assumes procedural justice leads to distributive justice - a classic normative fallacy. when you operationalize ‘chance of benefit’ using QALY metrics, you’re implicitly devaluing geriatric and disabled populations. the ASCO criteria are statistically valid but ethically colonial. you’re not allocating resources - you’re performing triage via algorithmic eugenics. and don’t get me started on ‘instrumental value’ prioritizing clinicians - that’s just institutional self-preservation masquerading as utilitarianism.

John Barron

January 3, 2026 AT 10:10While I appreciate the comprehensive overview of current ethical frameworks governing pharmaceutical allocation, I must respectfully assert that the absence of a standardized international metric for ‘years of life saved’ introduces significant inter-institutional variability. Furthermore, the reliance on electronic health record logging, while commendable, remains insufficiently interoperable across legacy hospital systems, thereby undermining auditability. A mandatory, federally mandated blockchain-based allocation ledger, encrypted and auditable by third-party bioethics auditors, would significantly mitigate moral hazard and enhance public trust. Additionally, I recommend the adoption of the WHO’s 2022 Global Drug Access Index as a baseline calibration tool.

Anna Weitz

January 5, 2026 AT 03:09they say no age or income bias but in practice the rich get the drug first because their doctors know how to push the system. the rest of us wait or die quietly. this isn’t fairness. it’s luck.

Gerald Tardif

January 5, 2026 AT 06:03you’re not alone. i’ve seen nurses cry after having to tell a 28-year-old mom she can’t get her next dose. but here’s the thing - hospitals that built those committees? they’re not perfect. but they’re trying. they’re training staff. they’re talking to patients. it’s messy. it’s hard. but it’s better than guessing. don’t give up on the system - help fix it. volunteer. push for transparency. show up at town halls. change doesn’t come from outrage alone. it comes from showing up, again and again.

Elizabeth Alvarez

January 7, 2026 AT 01:18the real conspiracy? the FDA’s ‘early warning system’ is built on data from manufacturers who are legally allowed to lie about production delays. they report shortages ‘six months in advance’ - but only after they’ve already stopped making the drug. the AI system? it’s trained on lies. the whole thing’s a charade. they want you to believe they’re fixing it - so you stop screaming. but the vials aren’t coming back. the companies aren’t being fined. the CEOs aren’t going to jail. and the patients? we’re just collateral damage in a market that values profit over life. wake up. this isn’t a glitch. it’s the design.